A World In Need of Beauty

Commentary

Not long ago, Elisabeth Sullivan, director of the Institute for Liberal Catholic Education, reflected on the most frustrating questions a teacher can be asked by a student: “Is this going to be on the test?” Or, “Do we have to know this?” These questions signal a disappointing failure to engage the mind of the student; they indicate a child whose mind sees knowledge and schooling only in utilitarian terms. Worst of all, these questions signal a child whose sense of wonder has not been activated. If I don’t “need” to know it, why bother? Love of learning does not drive the student, only utility and necessity. And they can be grim masters. Too many young people seem to have become jaded at too young an age (as if one should be at any age!). They have learned to value learning only for its utility: will this information help me get a good job, make money, and live a comfortable life? Why have the young become so jaded so soon?

Many reasons for this exist. We sometimes seem to live in a jaded, apathetic age. The ubiquity of entertainment and entertainment technology surely has something to do with the problem. There are so many easy ways to stimulate the senses: smartphones, social media, music videos, internet games and others. Yet, the sheer ease of the highs one gets from these sources can lead one to abjure the harder road to the pleasure that comes from higher goods. Why work years for the pleasure of reading St. Augustine in the original Latin when one can merely feel the more immediate pleasure of the online game or Tiktok video?

Worse still, our age is jaded in another way. Once the dream of the (good) teacher was to introduce students to the good, the true, and the beautiful. Yet, the teacher already finds major roadblocks in the path. How can he teach students to love the truth when so many are convinced of what Pope Benedict XVI called the “dictatorship of relativism.” How can they love truth when they are so convinced it does not exist? Our society has created a whole generation of little Pontius Pilates, each asking “what is truth”? Likewise, as Bishop Conley of Lincoln Nebraska asks, how can children today love the good? Too many have been convinced that goodness is subjective and relative. And this goes well beyond the young alone.

Speaking in the bitterness of disappointed expectations, the founder of Taoism, Lao-Tzu once seemed to argue for precisely this sort of society and people. A wise man, according to him, would not encourage excellence. Instead, the sage, he says:

“... empties [people’s] minds, fills their bellies, weakens their wills… He constantly (tries to) keep them without knowledge and without desire, and where there are those who have knowledge, to keep them from presuming to act (on it).”

In some ways, Lao-Tzu’s dream seems to be recognized today. How then are we to break through the modern malaise, ennui, and apathy? How are we to reach an apathetic and weary world?

Bishop Conley suggested that the answer was beauty.

“In a cultural environment bereft of wonder, beauty takes on an even greater importance than it would otherwise have. Something in the experience of beauty is almost undeniable, even for the person who rejects the idea of objective truth or goodness. Beauty can get through, where other forms of divine communication may not.”

Furthermore, in Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis suggested that catechesis should take note of the via pulchritudinis, the way of beauty. “Proclaiming Christ means showing that to believe in Him is not only something right and true, but also something beautiful, capable of filling life with new splendor and joy, even in the midst of difficulties.” Beauty, whether found in the beauties of great works of arts, the beauties of nature, or the beauties of excellent music, can still move the human heart in a world grown cold.

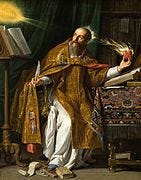

In Book X of his Confessions, St. Augustine offers his well-known and much loved reflection on Divine Beauty:

Late have I loved Thee, O Beauty so ancient and so new; late have I loved Thee! For behold Thou were within me, and I outside; and I sought Thee outside and in my unloveliness fell upon those lovely things that Thou hast made. Thou were with me and I was not with Thee. I was kept from Thee by those things, yet had they not been in Thee, they would not have been at all. Thou didst call and cry to my and break open my deafness: and Thou didst send forth Thy beams and shine upon me and chase away my blindness: Thou didst breathe fragrance upon me, and I drew in my breath and do not pant for Thee: I tasted Thee, and now hunger and thirst for Thee: Thou didst touch me, and I have burned for Thy peace.

To St. Augustine, God Himself could be addressed as Beauty, “so ancient and so new.” Yet, as he himself admitted, he long missed the Beauty that was God because he fixated too much on the beauty in things apart from God. We may face the same temptations as St. Augustine, to seek entertainment and pleasure apart from God. But if we resist this, we can instead see beauty as that which can lead us to God. Beauty may be our best way to break through the modern sense of ennui and apathy. And it is the Christians task to proclaim it to a weary world.

Great article! I think this is why images of the Blessed Virgin can be so electrifyingly potent -- they can hit us right in the heart. Her loveliness (fused with her gentleness) is so touching.