From Thence He Shall Come: Facing Fear of the Judgment

Meditation

Update: the author has added comments to clarify some merits of servile fear, so as not to imply that it is altogether without value.

The novena for All Souls has begun, and it’s that time: the time to begin praying more intently for the dead, and to reflect upon our own impending death.

There are two things we might fear after death: first, the idea of simply not existing (the atheist’s fear). And second, eternal suffering, never to end. In regards to the latter, then, we fear… judgment, the unfailing, unrevokable judgment pronounced by the Lord Himself. For in the Creed it is written,

From thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

“Judge” is a scary word, especially for Christians. When we die, we shall face what is called the “particular judgment” that each individual goes through: we will stand before the Judge Himself, from Whom we can hide nothing. The Roman Catechism says in no uncertain terms that we shall “receive sentence from the mouth of [our] Judge” when we die: all that we have said, done, or even thought “is subjected to the strictest scrutiny.” Knowing how sinful we are, the inevitability of this judgment might fill us with an immense terror. A Christian might fear death on account of fearing the utter shame of confronting himself, in addition to the possibility of going to hell.

“Mercy!” we cry. That word is a shield against our fear: it is held up by both the one who truly loves God and desires heaven, and by the one who lives a life of sin and does not wish to change. God is merciful and wishes us in Heaven; why then should we fear death, if He wants our eternal beatitude? Why should we fear death, if that is the only way we can enter heaven? Is there any reason to fear death and the judgment that follows?

Perhaps there is a reason to fear. Can we be fearless because we presume that God would never, in the end, send us to hell? Do we believe that surely love will never condemn us? No! That is not true mercy. Let us not fall into presumption, and into the heresy of an empty hell. Yes, we journey as pilgrim children toward God, and we recall the joyful welcome the Father gives to the Prodigal Child. But at the same time, we must fear and tremble at the thought of standing in front of the Judge, lest we become idle on the pilgrimage and cease walking along the path to heaven.

There is a baser fear and a higher fear; it is this distinction which tells us how to approach the thought of judgment. The first and most common fear is a low, even animalistic, servile fear. Servile fear is irrational and based on material, physical, or emotional impulses. Our bodies fear death, so we have preservation instincts. (The medievals called repentance based on fear of punishment, “attrition.”) And we fear people who have power over us because they may hurt or destroy us. We fear losing our jobs because we fear material discomfort, being unable to provide for ourselves and our families, and so on.

Of course, there is merit in fearing eternal punishment, if it inspires us to repentance. But if we are to be unafraid of death, we should seek the higher fear: fear of the Lord.

The fear of the Lord, holy fear, is the beginning of wisdom (Prov 9:10). Unlike servile fear, this fear is not controlled or directed by our passions, though it may sometimes evoke them. Instead of being driven by death-fearing impulses, fear of the Lord is awe and love before the One Who made us. It is also called filial fear: respect and obedience toward one’s Father.

How can we fear Him as we ought, with love, confidence, adoration, and reverence, instead of remaining in constant fear of punishment? An answer is to be found in the very fact itself that we shall be judged. After our death and judgment, we shall be sent to heaven, perhaps to purgatory on the way or, quod Deus avertat, to hell.

The reality of Hell shows us an extraordinary fact of our own existence: God gave us free will, and our choices matter. That God is a God of mercy is not a contradiction to the fact that hell is real, that others have gone there, and that I might go there. In The Light of Christ (2017), Fr. Thomas Joseph White, O.P. says that Hell shows us “the importance of personal responsibility… Our choices matter to God.” It is an incredible sign of God's love that we have any personal responsibility for where we will spend eternity. To God, we are infinitely less than a single ant is to us. We may as well be nothing, lower than a speck of dirt. And God does with us what He wills. Yet in God’s love, He made our choices matter.

God calls us to heaven, but He does not force us there.

However, lest we think too much of our free will, we must remember that our choices cannot bring us to heaven (and ultimately, that it is God who sends us to hell). No human being merits heaven in themselves–not even the tiniest infant or the holiest saint. No one is worthy of the One True God. It is God's love alone that permits our entry into heaven, not any worthiness on our part. It would be the supreme blindness of pride and presumption to say that we could somehow merit or deserve heaven. We cannot.

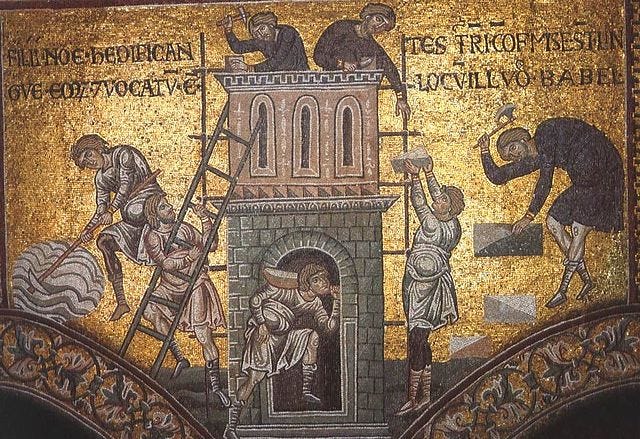

This seems, on the surface, rather frightening. We cannot work our way into heaven—to think so would be a form of the Pelagian heresy—and yet we very much wish we could, because our pride detests our own powerlessness. But when we try to climb the ladder on our own, we are constantly reminded of our own failings and inadequacies, which leads to despair. To believe that our work can build us a tower to heaven leads us to the hopelessness, destruction, and confusion—ultimately born of pride—that was present at the Tower of Babel.

But it is wonderful that we cannot work our way into heaven, for we would certainly fail. The Pelagian despairs of heaven because he thinks he can work his way there; but fortunately, he is wrong. Thank God we are so weak! He can perfect us and bring us there in our weakness. Oh Fount of Mercy! Instead of being cast immediately into hell because we lack all merit, we beg Your aid at every moment unto death, and we trust that You will condescend to hear us.

“From the earliest times,” Pope Benedict XVI wrote in Spe Salvi (2007), “the prospect of the Judgement has influenced Christians in their daily living as a criterion by which to order their present life, as a summons to their conscience, and at the same time as hope in God's justice. Faith in Christ has never looked merely backwards or merely upwards, but always also forwards to the hour of justice that the Lord repeatedly proclaimed.” Both our free will and our reliance upon God give us concrete reasons for hope. We might see the Last Judgment, then, with gratitude toward God, and with holy fear. For redemption is not simply a given. But it is offered to us if we live our lives in hope, facing every trial and temptation with gratitude toward, and reliance upon, the gifts which He has given us.