“My brain will not write anything today.”

We have all heard (and some of us say) things like this in our daily life. But is it really the kind of thing a Catholic should say? Is it really true that our brain is responsible for doing or not doing things for or with us?

No, it is not your brain that does anything. Neither is it just your soul. Rather, it is the composite of both body and soul which does something.

Still, some people will want to attribute things such as writers’ block specifically to their brains. They say: “my brain just doesn't want to work now,” or “my brain just isn’t cooperating.” They may say: if it is the body/soul which writes, then what about people with observable neurological issues (or something such as brain damage) that affect how one thinks? The soul obviously maintains its intellectual faculties (including after death) regardless of what has happened to the body, but there is clearly something in the brain connection that matters, at least, in terms of writing something.

Besides, when it comes to writer’s block, it could also be possible that one’s mind is operative, but a different faculty of the soul is the reason one can't write (such as the will). So, there are quite a number of complications to placing the blame when it comes to having difficulties with intellectual activities.

First, the brain is a part of the structure of the body. Unlike the soul, the brain exists solely as a material part of the human being. Even then, the brain is not itself an independent substance, a thing that exists in and of itself. That is to say, since the existence of a brain is predicated on the existence of a body, which the brain is part of and dependent upon, the brain is not a substance.

Next, it is the soul which is the active principle of the body; the soul animates us. Since the soul animates the body, not the other way around, the brain cannot do anything apart from the soul and the body. Thus, lest we commit a mereological fallacy (confusing a whole for one of its parts) we say that the body and soul are acting, not simply the body. The brain does not act on its own.

This helps us answer the question of what’s to blame for writer’s block. Fatigue or vacation mode can make it difficult to think, since the soul (subconsciously) seeks to help the human to survive; we require rest. So when we are on vacation, this is why we sometimes cannot write as efficiently or as well as we like. The soul is at work (or rather, stopping us from work). It is also possible that the physical limits of our brains as organs impede the kinds of things we can think.

As for neurological conditions, however, our matter (body) can have deficits, which give rise to privation (in this case, a lack or lessened ability), and thus impede the form from shaping the acts of the being. That is to say, the soul may be unable to do what it ought because it is composite with the body and directs what the body does. Color blindness, for example, is a privation in the organs of sense.

How does such privation apply to deciding whether the brain itself, or the body/soul composite as a whole, is the problem? In what instance would it be appropriate to say that human imperfection (e.g. a neurological issue), which is called by philosophers privation, is the reason for an intellectual problem rather than the mind? Let's say, for example, someone says he has an observable neurological issue (hence, a material, bodily issue) that affects how he thinks and/or acts, and that's why he has trouble writing an article. Would it be appropriate to blame his brain there?

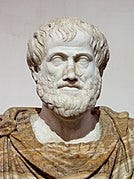

Human imperfection is a better explanation for a deficit when the soul is less able to act than it should by bodily dysfunctions (that is, to perform its functions of survival, sensing, thinking, etc). But for tiredness or rest, it is more a limitation of the kind of organism itself–a human limitation. After all, we are not angels. Things like tiredness, which affect our ability to work, are attributed to the limitations of our being human, not only to the body (or a body part) or to the soul. In any case, Aristotle says that rest is necessary, because any non-angelic sentient living being cannot be active at all times. Our organs have physical limits that prevent constant activity without damage being done to the organism.

In the end, blaming the brain isn't a good practice. Saying “My brain won’t do this” when we are talking about an intellectual task conveys an incorrect materialistic sense of the mind. And if there is true privation, it would better to say, “Due to a disorder of my brain, I am unable to write,” rather than saying that the brain won't write.

So, it is appropriate to place partial responsibility on the physical brain in certain contexts, but we should try to avoid doing so, because it's misleading. Cognition should not be reduced to a material process going on inside our skulls. As Christians, we know that man is body and soul in one. We are not our brains, and we shouldn’t lead others to believe that man is the brain.