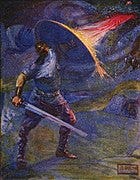

There Be Dragons... and Knights!

Commentary

The Great English Essayist, G.K. Chesterton, is sometimes misquoted as having written, “Fairy tales do not tell children that dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children that dragons can be killed.” Phrased thus, the quotation is apocryphal, though the spirit is entirely Chestertonian. James Grant traced the original Chesterton quotation as:

Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.

In the same vein, C.S. Lewis, in his essay, “Three Ways of Writing for Children,” wrote that “since it is so likely that [children] will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage.”

The old fairy tale writers knew this: that we lived not only in a material universe, but in a moral universe. These included medieval tales of King Arthur and Robin Hood, epics like Beowulf or The Song of Roland, modern fantasy writers like George MacDonald, C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien, and even, if we not be too proud not to notice them, nursery tales like “The Three Pigs” or “The Three Billy Goats Gruff.”

A charming recent take on the traditional knight and dragon story for children is Jennie Bishop’s The Squire and the Scroll, a traditional story of a young squire on a quest to slay a dragon and recover a lost lantern, while guarding his pure heart. The dragon is suitably fearsome and wicked, the squire brave and virtuous, and the danger entirely convincing. Like the previous authors and tales, it captures the age-old battle of good and evil, courage and peril, devotion and steadfastness. These stories warned children to be alert, that there were cruel enemies in the world, but to be also of good heart, for there were also heroes to defeat them.

And somewhere, our society lost this. Another dragon story for children, The Knight and the Dragon, by the usually delightful Tomi DiPaola, turns the normal fairy story on its head. In his story, the knight and dragon bumble halfheartedly into battle with each other under the pressure of traditional expectations before giving up the battle and deciding to get along and open a barbecue restaurant together. Other examples abound. The popular How to Train Your Dragon Movies feature an apparent war between dragons and humans, only to end when the viewer learns the dragons were simply misunderstood. Modern takes on fairy tales, like Maleficent, often turn the villains into misunderstood, complicated figures. The Shrek films may perhaps have been meant as parody or satire; but when satire becomes the norm, is it satire any longer?

The problem is that children are not only denied great heroes, but they are also denied great villains. What was so offensive about the movie Frozen was not just that the heroes were not very heroic, but that the villain was not particularly villainous; there, the villain was ultimately no more than a whiny adolescent boy. Evil is erased and becomes a series of misunderstandings, the only real problem, pace How to Train Your Dragon, or Shrek, is intolerance and narrow-mindedness. None of this is surprising to a society looking to redefine and change the meaning of virtue. Traditional evil is not really evil. Traditional good might not really be good.

Against this stands the knight in the traditional fairy story, facing the dragon sword in hand and ready to prove with his body that good is good, evil is evil, and never the twain shall meet, save on the field of battle. He assures the child, (and adult, for that matter), that a lost cause need not be lost if the hand be steady and the heart steadfast. For the dragon not only represents the presence of genuine evil, but of supernatural evil. The hero must fight to his utmost, but if he is to conquer, it must often be, like Frodo at the cracks of Doom, with the help of divine grace or providence. Sleeping Beauty’s Prince Phillip is given a magical sword and shield to face his dragon, supernatural weapons and help to face supernatural evil.

This is the greatness of fairy stories. Despite the attempts of the modern world to deny it, evil looms large both in the classic tales and in our world. The evil is often not merely natural, but supernatural: that is why it so often seems unconquerable. But it is not, as the fairy stories remind us. As Chesterton said, if there is a dragon, there is also a St. George to kill it. And by virtue and grace, it is a battle that no child, or adult, will fight alone.