This June Remember: Pride is Still a Sin

Commentary

In a recent history class, I was discussing late medieval monasticism, in particular, the Benedictine monks and Franciscan friars in comparison. In the course of our discussion, we talked about the monastic vows: poverty, chastity, and obedience. I asked my ninth graders which of those vows they thought was considered most difficult in the Middle Ages. Predictably, they all answered, “chastity.”

Therefore they were quite surprised when I explained to them obedience was actually seen as the most difficult vow of the monk. For obedience meant the surrender of the monk’s own will to that of his abbot.

I was recently reminded of one amusing, but instructive incident in St. Thomas Aquinas’s life. When he was an older man, a young brother came and ordered him to come shopping with him and carry his groceries. The young friar had been told by his superior to go shopping and to take with him the first monk he met. That happened to be the angelic doctor himself! St. Thomas realized the monk had not recognized him and meekly set off after him, eventually huffing and puffing along. This continued until they met some others along the way who recognized St. Thomas and the game was up. The young friar was mortified that he had made the famous university Professor carry his groceries, but St. Thomas explained that they had both behaved correctly… for both had been obedient to the command of their superior.

Part, or perhaps much of the reason that obedience was seen as so important and so difficult was that it was directly opposed to the sin of pride. Pride, in the middle ages, was called the chief of the vices. Sometimes it was listed as simply the worst of the seven deadly sins and sometimes it was listed by itself as a kind of super-sin above the seven. But either way, pride was the worst and most deadly fault.

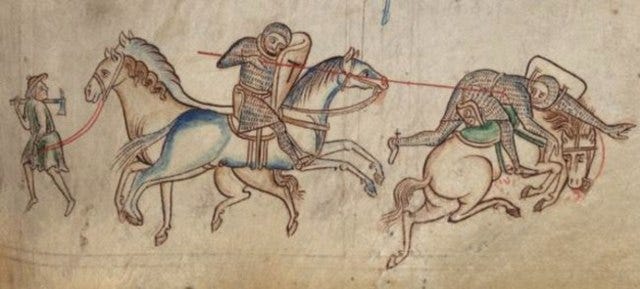

It was also seen as the fault to which the warrior class, the bellatores, the knights and their lords, was most prone. Indeed, pride was often pictured as a knight riding on horse. This should not surprise; knights and their lords were the among the highest classes in medieval society; they were certainly used to having their own way and were often seen as prone to the sins of vanity and its more serious cousin, pride. One imagines the knight on his horse, riding above the rest of society and looking down upon it. Even today, when we speak of a proud man, we often speak of someone who looks down on other people. And such was the knight on horse, looking down on society.

At this point in the discussion, one of my students objected by telling me she disagreed. She did not think pride was serious or a sin at all. When I asked her why, her answer indicated that she saw pride more as a species of self-esteem, i.e., a person should be proud of himself and have a high self-esteem. We continued the discussion; I suggested that when people in the Middle Ages referred to pride, they did not mean what many modern people might think of as a measured self-esteem, but something more along the lines of arrogance. I am not sure she was entirely convinced.

Others in our modern world go even further than my student. Far from being seen as a danger, something to be ashamed of or to repent, pride, in our modern world, has come to be seen as something positive, even something to celebrate. We are approaching an entire month (June) that has been rebranded as “pride month”: a celebration of sexual deviancies and vices.

And yet, it is hard not to think the medievals were right. The Fatima visionary Jacinta said that the Blessed Mother told her that more souls go to hell for the sins of the flesh than any other sin, but there is also a particular reason why, though more souls may go to hell for the sins of the flesh, that pride remains the worst sin. One writer put it this way: the sins of the flesh make us animals, but pride makes us into devils.

For pride was the sin by which the devil fell from heaven. Pride means not only enmity with other men, but with God, for the proud man is always looking down on others (like the medieval knight on horse). As long as one is looking down on others, he cannot see He Who is above him.

Pride is dangerous for another reason. A man can commit the sins of the flesh and be disgusted with himself. That disgust may be his conscience talking, the small voice inside that tells a man he has debased himself, and that he ought be ashamed of himself. That disgust and shame may thus inspire him to regret and repentance.

This is why pride has become so popular a sin, and so big a problem, in the modern world. This is why some now even take an entire month to celebrate it. If our conscience can cause us to feel disgust over the sins of the flesh, pride is dangerous because pride silences that voice. As a man learns to take pride in his sins, that pride becomes a noise that silences the voice of conscience. Pride becomes an armor that “protects” from admitting our own sinfulness. C.S. Lewis’s character Screwtape praised noise for drowning scruples and morals; pride is the noise, the shouting meant to drown out the quiet voice of conscience, which is really God.

This June, there will be a great deal of shouting and noise. Corporate advertising will shove pride and (misappropriated) rainbows in our faces; pride parades and festivals will dominate the news. All that noise and all that pride all are meant to drown out the voice of conscience.

If pride and indulgence are to be celebrated, then we can only respond with self-denial and prayer. When the flesh tempts, we should practice chastity and temperance by fasting; when pride tempts, we should practice humility in silence and prayer.

Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, have mercy on us.